Dear Dr. Scribblerstamps:

I am a member of First Reformed Church in the first block of East King Street. Some of the members of the church have been talking about a counterfeiting operation behind the church in the late 19th century. We don’t know much about it.

We do know that it involved the blue tobacco stamps that showed that the buyer had paid the federal tax on tobacco products. Can you tell more of the story?

William Sloyer

East Lampeter Township

Dear William:

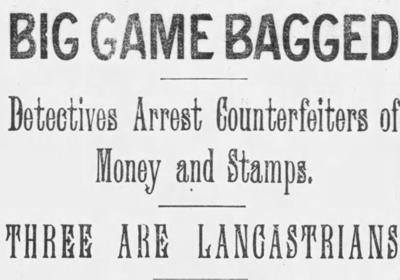

Lancaster’s most famous counterfeiters generally are remembered for the $100 bills they manufactured. Actually, they weren’t so good at that. The fake money tripped them up.

The tobacco stamps were the big deal. They successfully printed them for four years before they got caught.

Fifteen U.S. Secret Service agents arrested the counterfeiters 125 years ago last month. The main operation was in a cigar factory at Christian and Grant streets, just south of (or “behind,’’ as you say) First Reformed Church.

On April 22, 1899, the Lancaster Intelligencer Journal devoted most of its front page and much of its second page to the arrests three days earlier. The Secret Service at the time described the crime as “the best counterfeiting scheme’’ ever seen in this country.

The two main culprits were William M. Jacobs, one of Lancaster’s chief buyers of leaf tobacco, and W.L. Kendig, a tobacco buyer in business with his father, Dr. B.S. Kendig. Several other men were in on the scheme, including one of Kendig’s employees and two Philadelphia engravers.

The illegal operations began in 1896 when Jacobs and Kendig began creating fraudulent blue tobacco stamps for the cigars they sold. By making their own stamps, they did not have to purchase government stamps, which represented a tax on tobacco.

Government agents ultimately determined that Jacobs and Kendig sold about 45 million cigars with fake tobacco stamps, thus defrauding the government of about $100,000.

Not satisfied with that haul, the conspiratorial counterfeiters began manufacturing bogus $100 bills. They had planned to create sufficient bills to flood the market and ultimately make millions of dollars.

Unlike the tobacco stamps that had fooled everyone for years, the phony money had a fatal flaw. A sharp-eyed U.S. Treasury employee in Philadelphia determined the seal on one of the $100 bills was off-color.

By that time, the investigation of the tobacco-stamp caper was well underway. Secret Service agents working undercover associated the two counterfeiting operations. They arrested the culprits before more than a few dozen of the $100 bills had moved into circulation.

In June 1900, Jacobs and Kendig were each sentenced to 12 years in prison for their crimes. Others involved in the scam received lesser sentences.

In July 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt pardoned Kendig and Jacobs after they had served less than half of their sentences. The Lancaster Examiner observed that both men “were expecting a pardon, as they knew powerful influences were at work in their behalf.’’

Dear Dr. Scribblermighty:

I read your remarks about Joe Greenstein, the Mighty Atom, in the May 19 Scribbler column. You might be interested to know that the truck your reader remembers seeing at Root’s, as well as many other artifacts from Greenstein’s career as a strongman, are on display at the Boyertown Museum of Historic Vehicles.

Calling ahead (610-367-2090) is advised, as they do rotate exhibits in and out from time to time.

Howard Horn

Lancaster

Jack Brubaker, retired from the LNP staff, writes “The Scribbler’’ column every Sunday. He welcomes comments and contributions at scribblerlnp@gmail.com.

![History of Root's Country Market strongman, mystery ‘pyramid’ near Washington Boro [The Scribbler]](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/1/a5/1a564a4e-1307-11ef-b3e8-c31e187ab1a5/6645316de66af.image.jpg?resize=150%2C109)

![Add scenic bicycling to Lancaster County’s distinguishing features [The Scribbler]](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/6/37/63732530-b3c7-11ed-a462-f7d186d41b42/63f7e52ea5792.image.jpg?resize=150%2C111)

![Why a national Underground Railroad list recognizes local Quakers’ graves but not their house [The Scribbler]](jpg/6631912cc3a5e.imageccc7.jpg)